Why Batteries Go Bad

If lithium ion batteries are continually flowing lithium ions and electrons through cycles discharging energy and recharging then how do they stop working? Over time due to this continual charging and discharging lithium ions bond to the electrodes and less and less lithium ions are available for the battery system to use thus degrading the battery and causing it to carry charge for less amounts of time. This process commonly occurs when intercalation, or the insertion of lithium ions into the graphite or cobalt electrode, is happening at a slower rate than lithium ions are being sent over forcing the excess lithium ions to plate and become solid. Plating can also occur if the reaction is going too slowly as it will turn to lithium metal before reaching the electrode in this case. This can be very detrimental and dangerous to the battery. Plating potentially causes short circuiting and causing a buildup of heat and oxides caused by thermal run away from the short circuiting, a dangerous combination. Plating in fact is more likely to occur at low temperatures than the high temperatures. Degenerative conditions are normally caused by improper use such as fast charging rates and treatments of the battery such as running them too much or at higher temperatures than the batteries are designed for. Those situations increase the kinetics of the reactions in the batteries and therein lies what causes the battery to go bad. In fact lithium-ion batteries in EV vehicles can last anywhere from “5 to 20 years depending on a many factors”(ACS 2013).

How Can We Get The Most Out of Lithium-Ion

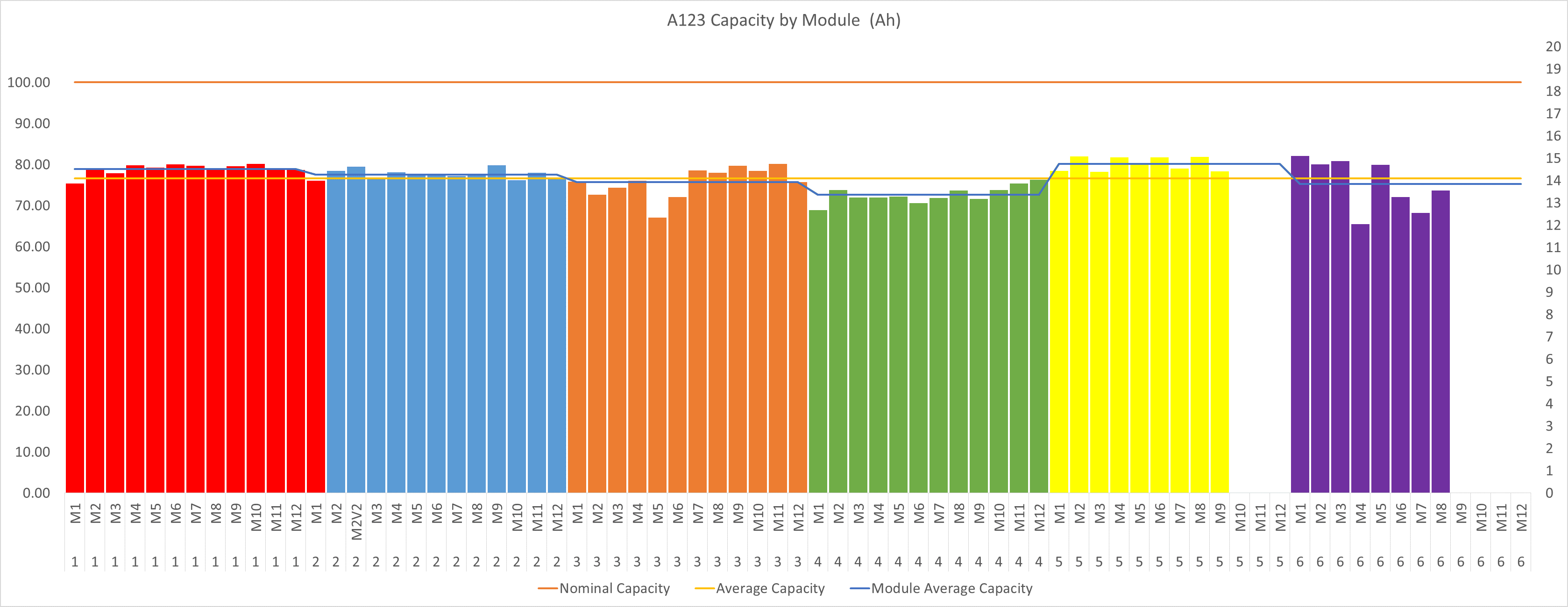

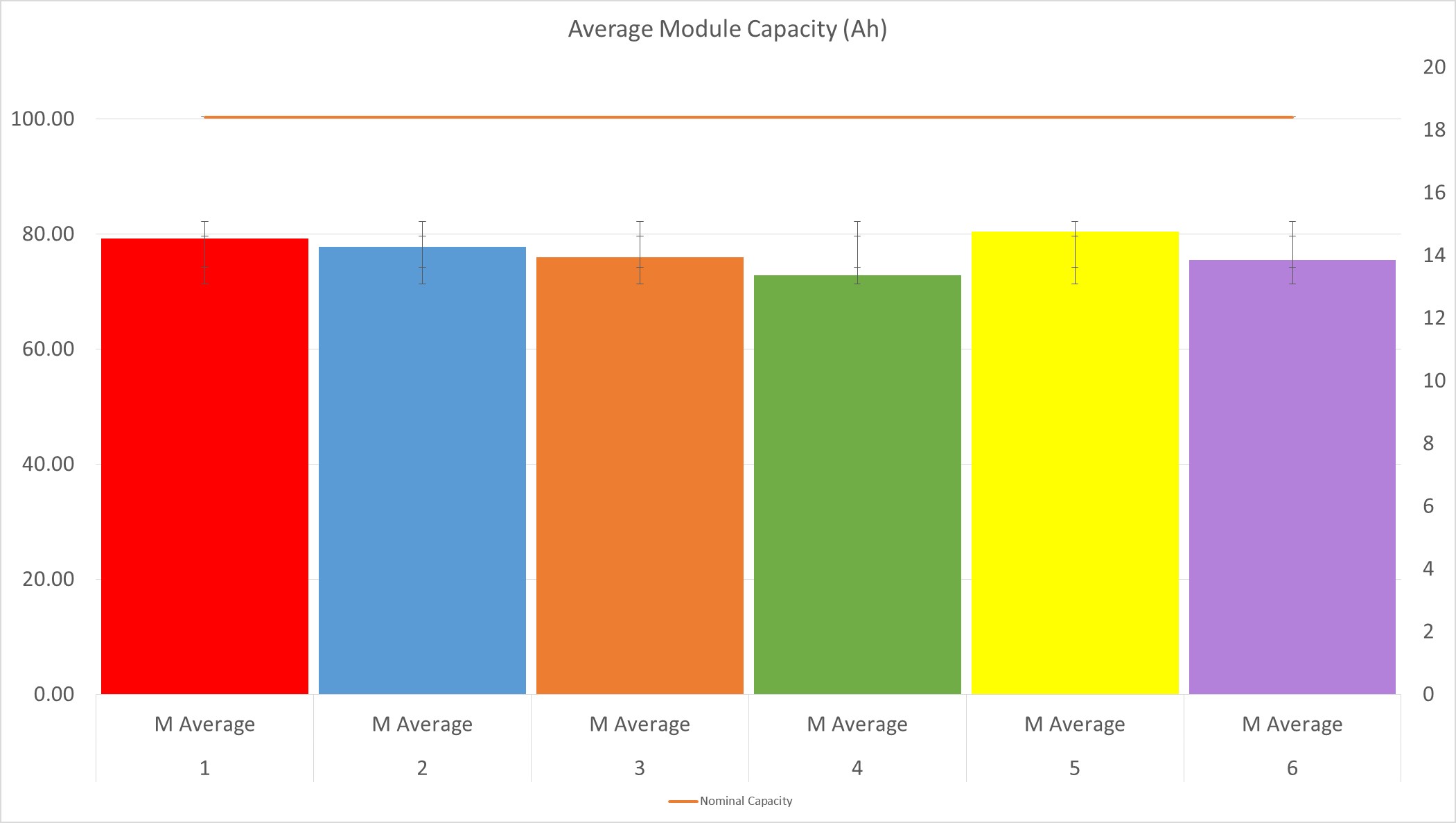

Even with this large potential span of battery life there are many other options to take after the initial lifetime is “over”. Many researchers are looking into the potentials of used EV lithium-ion batteries such as the University of California San Diego, or old hybrid metro bus batteries from the local King County Metro buses at the University of Washington. Specifically looking at the University of Washington’s supply of batteries there is still plenty of life left in these batteries. After testing 4 modules of batteries composed of 8 batteries in parallel in series of 12 the average capacity left has been found to be nearly 77% left. This was determined by running the modules of parallel batteries through cycles of deep charging and discharging while recording what the current in ampheres/hours was discharged. Using this data and the nominal voltages and capacity supplied by A123 batteries found here A123 Battery Info the batteries current capacity was determined.

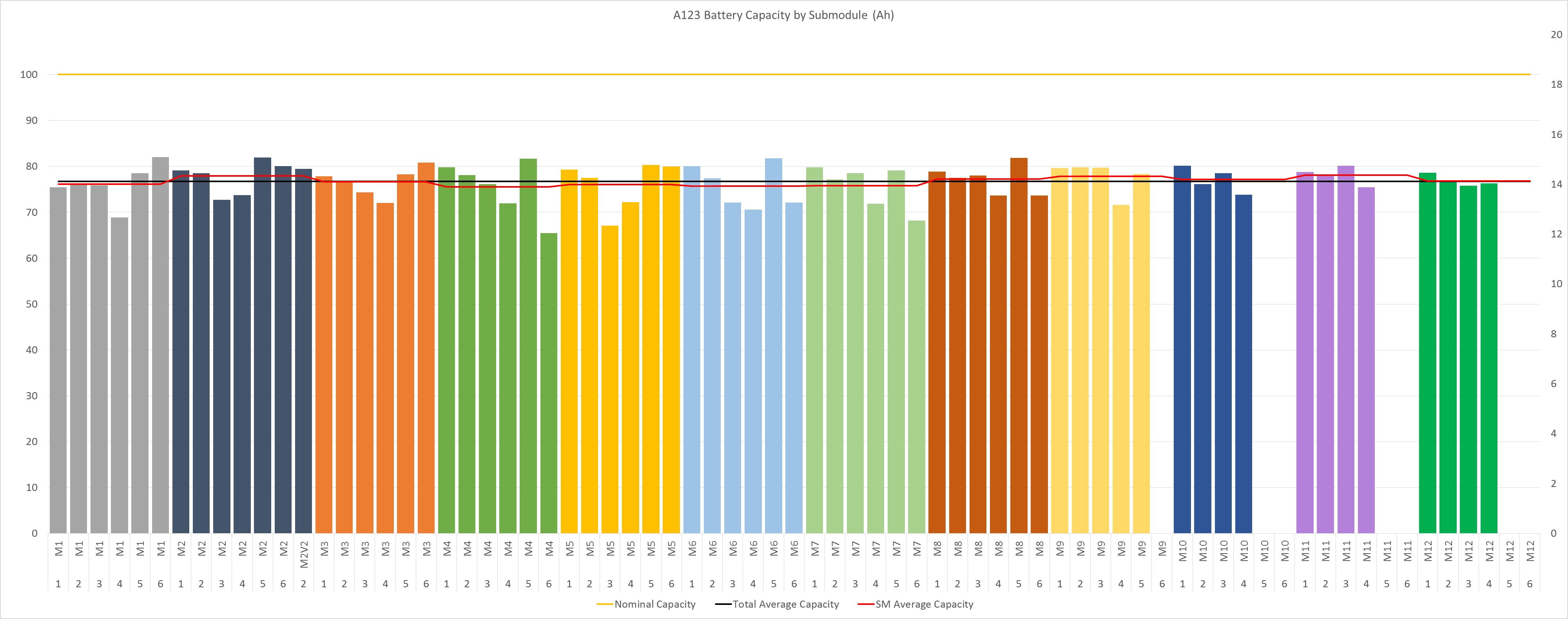

The graphs on the left show the data found during the testing of the batteries capacities. The first graph shows that within each battery module it would seem that one submodule of the module is the “bad apple” thus forcing the other submodules to pick up the slack and causing them to decline as well. This is also seen when looking at the modules average as a whole in the second graph. When considering the metro bus’s battery system having one bad module will decrease the voltage output making the signal go off saying the batteries are bad and that they can no longer be used as well as cause the other modules in the bus to work harder and lose capacity and usefulness quicker. The significance of find which module and then which submodule is causing the reduction in voltage is only the first step in prolonging the battery’s life. One battery in the entire submodule could be dragging the whole bus down. Further research into determining which battery causes this is needed as the only way to find out as of now is to entirely break apart the battery module and all 96 batteries. If a system is created that could target these batteries they could be made to be extremely efficient. Graph three tells us that there is not an inherent pattern for which submodule tends to go bad first or have to do more work supporting the need to be able to identify the battery the causes these problems and prolong the life of the remaining batteries by removing or replacing the deteriorated battery also supporting the need for better characterization techniques of the batteries.

Determining which battery has gone astray may seem beneficial to the metro and not for secondary use at first glance. While the battery modules lives could be extended on each bus with proper testing at incremented times most likely replacing the battery would not supply enough energy to continue using the current ones to accelerate and power buses around cities and regions. Replacing or removing the battery for grid storage purposes becomes key however since if it is it not it will only continue to perform its harmful effects to the other batteries and causing the storage on our grid to be less effective. With a few extra steps these batteries that have a large amount of life left could have even more.

Batteries that have been used and discarded by public and private users that still contain large amounts of life left are great, but what can we use them for? A few areas are being looked into for potential secondary use starting with the power grid. The grid is composed of some very old and proven ways to generate and store electricity, it’s known as hydroelectric power, being able to let water flow down and turn turbines to create energy and then even pump that water back up to create even more energy and power is an extremely useful technology. However, one simply cannot use that technique with solar or wind power. Solar and wind power not only have that issue but they also have peak times of day in which electricity is being created, and depending on the location this could be in the middle of the night when peak demand from electricity is long past. If this is the case then why haven’t power companies begun using some form of storage system? Batteries such as lead acid have been proven very successful for personal home solar storage but let’s keep in mind that that is for personal storage. Lead acid would take up way too much space to store all the energy that solar plants provide for cities and states; which leads us to the next kind of chargeable battery, lithium-ion.

Lithium-ion batteries would make great battery storage options for all these solar and wind farms and in many cases they already do, Minster Ohio’s solar plant is already going to be implementing this technology as well as New York City, each starting this year. Mainly these huge groupings of batteries will be aimed at helping the cities managed their peak power hours, when energy is being used the most and power companies at times have difficulty keeping up. But that’s not the only thing lithium ion batteries could be used for, other than on the grid lithium-ion is extremely light, portable, and carries a high energy density with it making several places such as hospitals or computer data storage areas, or anything that uses electrical equipment good places to have backup energy storage through lithium ion batteries.

Now with all of this being thrown out on the table making lithium-ion look all so glorified and amazing there are a few main reasons they are not being implemented for all these uses yet. The biggest and most important one at the moment is cost. Lithium-ion is expensive. In fact the whole reason the University of Washington has these leftover lithium ion batteries is because Metro is trying to find ways to cut costs on recycling these batteries so off to a secondary use for research they went. But if someone wanted to explore purchasing lithium ion batteries for grid or backup generator use this is a source that could potentially fuel the clean and green reusable energy movement. In 2014 16.9% of all metro busses across the United States were hybrid, using batteries like King County Metro’s. Imagine if these state companies and then the private auto companies started selling these old batteries. The cost to create and purchase EV cars or hybrid and electric busses would drop as they would be selling the old batteries to be placed on the grid or as backup generators which would then potentially lower electricity costs and modernize the ever so outdated grid we have. Secondary use of lithium-ion batteries might not only be a good clean energy idea, but in the future could be a very economically feasible and stimulating idea.